Chapter 2 Cancer as deregulation of complex machinery

Does not the entireness of the complex hint at the perfection of the simple?

Edgar Allan Poe (Eureka, 1848)

Armed with all these models, whether statistical or mechanistic, we are going to look at cancer, a particularly complex system that fully justifies their use Since the first chapter recalled how important prior knowledge of the phenomenon under study is for designing models, whatever their nature, this chapter will briefly summarize some of the most important characteristics of this disease before returning to the models themselves in the next chapter. Without aiming for exhaustiveness, and after an epidemiological and statistical description, we will focus on the most useful information for the modeler, i.e., the underlying biological mechanisms and available data.

Figure 2.1: Cancer is an old disease. Rembrandt, Bathsheba at Her Bath, c. 1654, oil on canvas, Louvre Museum, Paris

2.1 What is cancer?

Cancer can be described as a group of diseases characterized by uncontrolled cell divisions and growth which can spread to surrounding tissues. Descriptions of this disease, especially when associated with solid tumors, have been found as far back as ancient Egyptian documents, at least 1600 BC and we know from the first century A.D. with Aulus Celsus that it is better to remove the tumors and this as soon as possible (Hajdu 2011a). Progress will accelerate during the Renaissance with the renewed interest in medicine, and anatomy in particular, which will advance the knowledge of tumor pathology and surgery (Hajdu 2011b). The progress of anatomical knowledge has also left brilliant testimonies in the field of painting, which make the renown of the Renaissance today. The precision of these artists' traits has also allowed some retrospective medical analyses, some of them going so far as to identify the signs of a tumor in some of the subjects of these paintings (Bianucci et al. 2018). Such is the bluish stain on the left breast of the Bathsheba painted by Rembrandt (Figure 2.1) which has been subject to controversial interpretations, sometimes described as an example of "skin discolouration, distortion of symmetry with axillary fullness and peau d'orange" (Braithwaite and Shugg 1983) and sometimes spared by photonic and computationnal analyses (Heijblom et al. 2014). The mechanisms of the disease only began to be elucidated with the appearance of the microscope in the 19th century, which revealed its cellular origin (Hajdu 2012a). The classification and description of cancers is then gradually refined and the first non-surgical treatments appear with the discovery of ionising radiation by the Curies (Hajdu 2012b). The 20th century is then the century of understanding the causes of cancer (Hajdu and Darvishian 2013; Hajdu and Vadmal 2013). Some environmental exposures are characterized as asbestos or tobacco. Finally, the biological mechanisms become clearer with the identification of tumor-causing viruses and especially with the discovery of DNA (Watson and Crick 1953). The foundations of our current understanding of cancer date back to this period, which marks the beginning of the molecular biology of cancer. It is this branch of biology that contains the bulk of the knowledge that will be used to build our mechanistic models, and it will be later detailed in Section 2.3.

One of the ways to read this brief history of cancer is to see that theoretical and clinical progresses have not followed the same timeframes. The medical and clinical management of cancers initially progressed slowly but surely, and this in the absence of an understanding of the mechanisms of cancer. Conversely, the theoretical progress of the last century has not always led to parallel medical progress, except on certain specific points. The interaction between the two is therefore not always obvious. The transformation of fundamental knowledge into clinical impact is therefore of particular importance. This is what is called translational medicine, the aim of which is to go from laboratory bench to bedside (Cohrs et al. 2015). It is in this perspective that we will analyze the mechanistic models studied in this thesis. Their objective is to integrate biological knowledge, or at least a synthesis of this knowledge, in order to transform it into a relevant clinical information.

2.2 Cancer from a distance: epidemiology and main figures

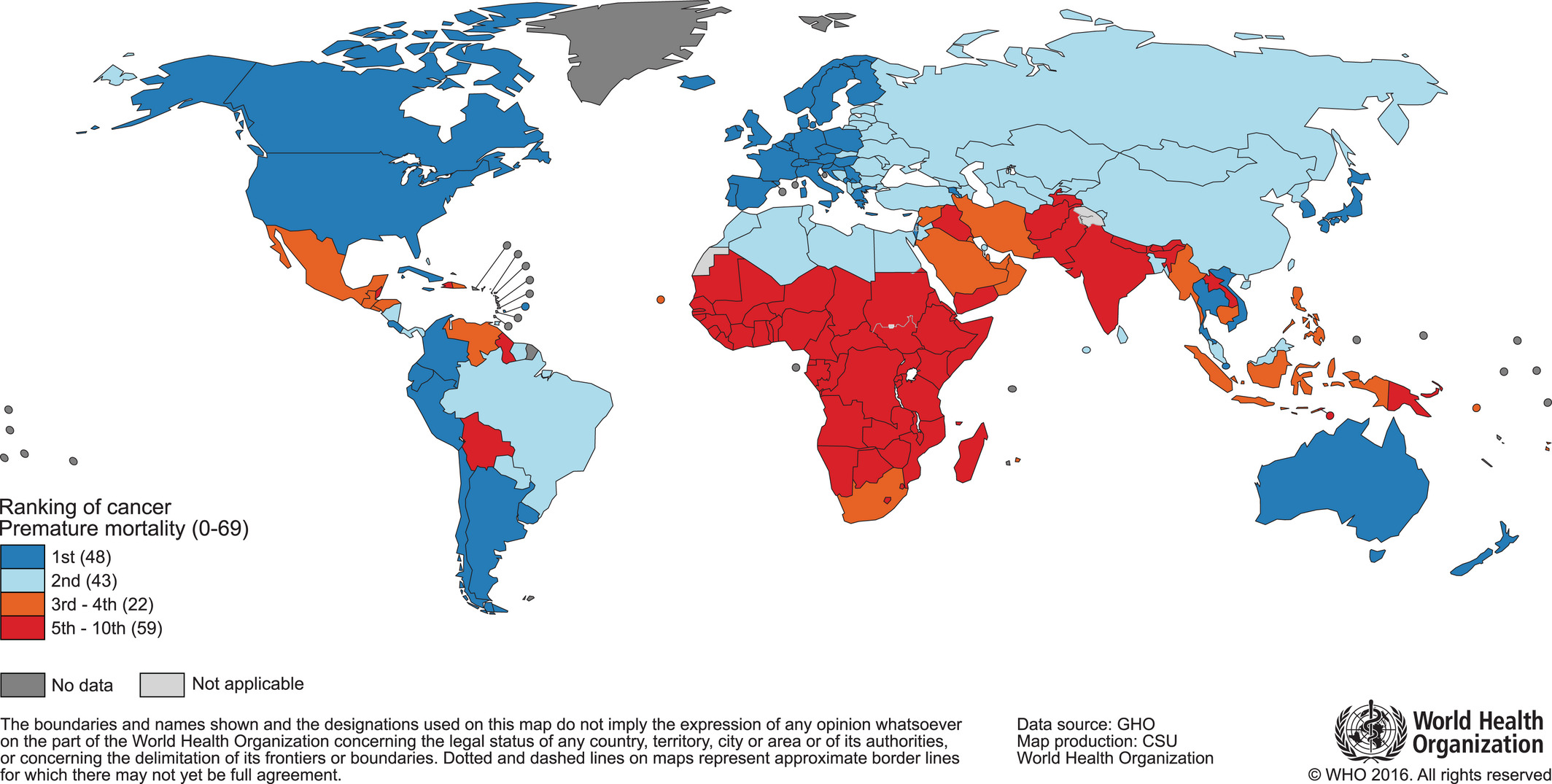

Before going down to the molecular level, it is important to detail some figures and trends in the epidemiology of cancer today. Following the description in the previous section, cancer is first and foremost defined as a disease. Considered to be a unique disease, it caused 18.1 million new cancer cases and 9.6 million cancer deaths in 2018 according to the Global Cancer Observatory affiliated to World Health Organization (Bray et al. 2018). However, these aggregated data conceal disparities of various kinds. The first one is geographical. Indeed, mortality figures make cancer one of the leading causes of premature death in most countries of the world but its importance relative to other causes of death is even greater in the more developed countries (Figure 2.2). All in all, cancer is the first or second cause of premature death in almost 100 countries worldwide (Bray et al. 2018). These differences call for careful consideration of the impact of population age structures and health-related covariates.

Figure 2.2: World map and national rankings of cancer as a cause of premature death. Classification of cancer as a cause of death before the age of 70, based on data for the year 2015. Original Figure, data and methods from Bray et al. (2018).

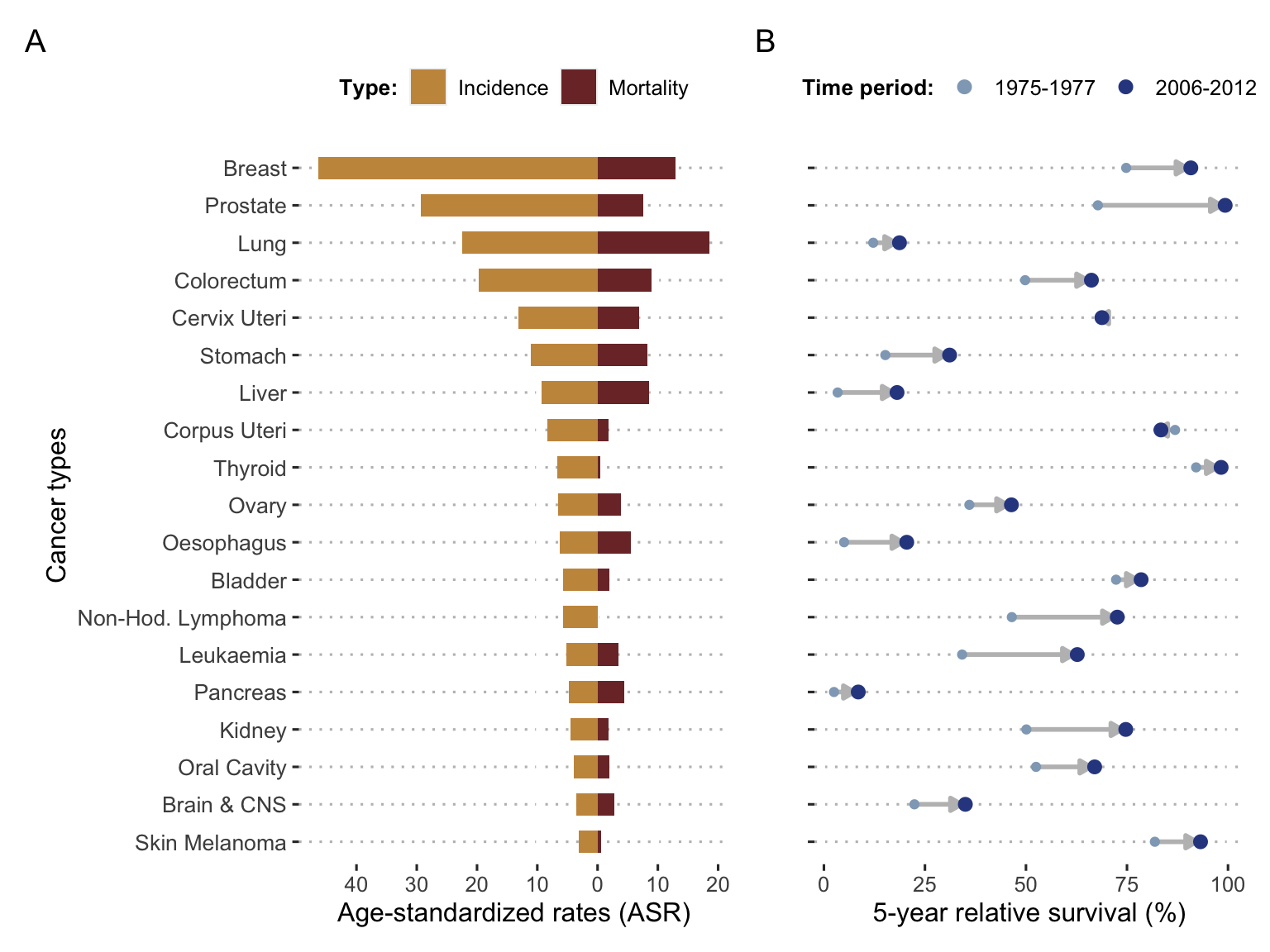

A second disparity lies in the different types of cancer. If we classify tumors solely according to their location, i.e., the organ affected first, we already obtain very wide differences. First of all, the incidence varies considerably (Figure 2.3A)). Cancers do not occur randomly anywhere in the body and certain environments or cell types appear to be more favourable (Tomasetti and Vogelstein 2015). Mortality is also highly variable but is not directly inferred from incidence. Not all types of cancer have the same prognosis (Figure 2.3A and B) and survival rates (Liu et al. 2018). Although breast cancer is much more common than lung cancer, it causes fewer deaths because its prognosis is, on average, much better. The mechanisms at work in the emergence of cancer are therefore not necessarily the same as those that will govern its evolution or its response to treatment. And still on the response to treatment, Figure 2.3B highlights another disparity: not only are the survival prognosis associated with each cancer very different, but the evolution (and generally the improvement) of these prognoses has been very uneven over the last few decades. This means that theoretical and therapeutic advances have not been applied to all types of cancer with the same success. It is one more indication of the diversity of cancer mechanisms in different tissues and biological contexts, which make it impossible to find a panacea, and which, on the contrary, encourage us to carefully consider the particularities of each tumor, both to understand them and to treat them. Under a generic name and in spite of common characteristics, the cancers thus appear as extremely heterogeneous. And to understand the sources of this heterogeneity, it is necessary to consider the disease on a smaller scale.

Figure 2.3: Incidence, mortality and survival per cancer types. (A) World incidence and mortality for the 19 most frequent cancer types in 2018, expressed with age-standardized rates (adjusted age structure based on world population); data retrieved from Global Cancer Observatory. (B) Evolution of 5-years relative survival for the same cancer types based on US data from SEER registries in 1975-1977 and 2006-2012; data retrieved from Jemal et al. (2017).

2.3 Basic molecular biology and cancer

If it is not possible and desirable to summarize here the state of knowledge about the biology of cancer, we are going to give a very partial vision focused on the main elements used in this thesis, thus aiming to make it a self-sufficient document. The details necessary for a finer and more general understanding can be found in dedicated textbooks such as Alberts et al. (2007) and Weinberg (2013).

2.3.1 Central dogma and core principles

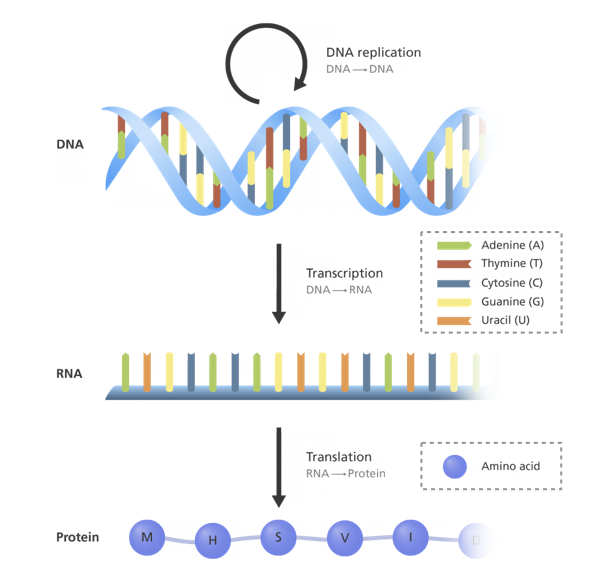

Some of the principles that govern biology can be described at the level of one of its simplest element, the cell. Let us consider for the moment a perfectly healthy cell. It must ensure a certain number of functions necessary for its survival and, sometimes, for its division/reproduction. These functions are encoded to a large extent in its genetic information in the form of DNA, which is stable and shared by the different cells since it is defined at the level of the individual. Most biological functions, however, are not performed by DNA itself which remains in the nucleus of the cell. The DNA is thus transcribed into RNA, another nucleic acid which, in addition to performing some biological functions, becomes the support of the genetic information in the cell. The RNA is then itself translated into new molecules composed of long chains of amino acid residues and called proteins. They are the ones that execute most of the numerous cellular functions: DNA replication, physical structuring of the cell, molecule transport within the cell etc. A rather simplistic but fruitful way to understand this functioning is to consider it as a progressive transfer of biological information from DNA to proteins, which has sometimes been summarized as the central dogma of the molecular biology (2.4), first stated Francis Crick (Crick 1970).

Figure 2.4: Central dogma of molecular biology. Schematic representation of the information flow within the cell, from DNA to proteins through RNA, more precisely described in this video (Image credit Genome Research Limited).

However, many changes would be necessary to clarify this scheme and the uni-directional nature was questioned early on. Above all, a large number of regulations interact with and disrupt this master plan. The genes are not always all transcribed, or at least not at constant intensities, interrupting or varying the chain upstream. This modulation in the transcription of genes can be induced by proteins, called transcription factors. After a gene transcription, its expression can still be regulated at various stages. RNAs can also be degraded more or less rapidly. RNAs can be reshaped in their structure during their maturation by a process called splicing, which varies the genetic information they carry. Finally, proteins are subject to all kinds of modifications referred to as post-translational, which can change the chemical nature of certain groups or modify the three-dimensional structure of the whole protein. For instance, some proteins perform their function only if a specific amino acid residue is phosphorylated. In addition, these modifications can be transmitted between proteins, further complicating the flow of information. All these possibilities of regulation play an absolutely essential role in the life of the cell by allowing it to adapt to different contexts, situations and development stages. From the same genetic material, a cell of the eye and a cell of the heart can thus perform different functions. Similarly, the same cell subjected to different stimuli at different times can provide different responses because these molecular stimuli trigger a regulation of its programme. But all these regulatory mechanisms can be corrupted.

2.3.2 A rogue machinery

With the above knowledge we can now return to the definition of cancer as an uncontrolled division of cells that can lead to the growth of a tumor that eventually spreads to the surrounding tissues. Therefore, this corresponds to normal processes, like cell division and reproduction, that are no longer regulated as they should be and are out of control. Experiments on different model organisms have gradually identified genetic mutations as a major source of these deregulations (Nowell 1976, Reddy et al. (1982)) until cancer was clearly considered as a genetic disease making Renato Dulbecco, Nobel Laureate in Medicine for his work on oncoviruses, say:

If we wish to learn more about cancer, we must now concentrate on the cellular genome.

(Dulbecco 1986).

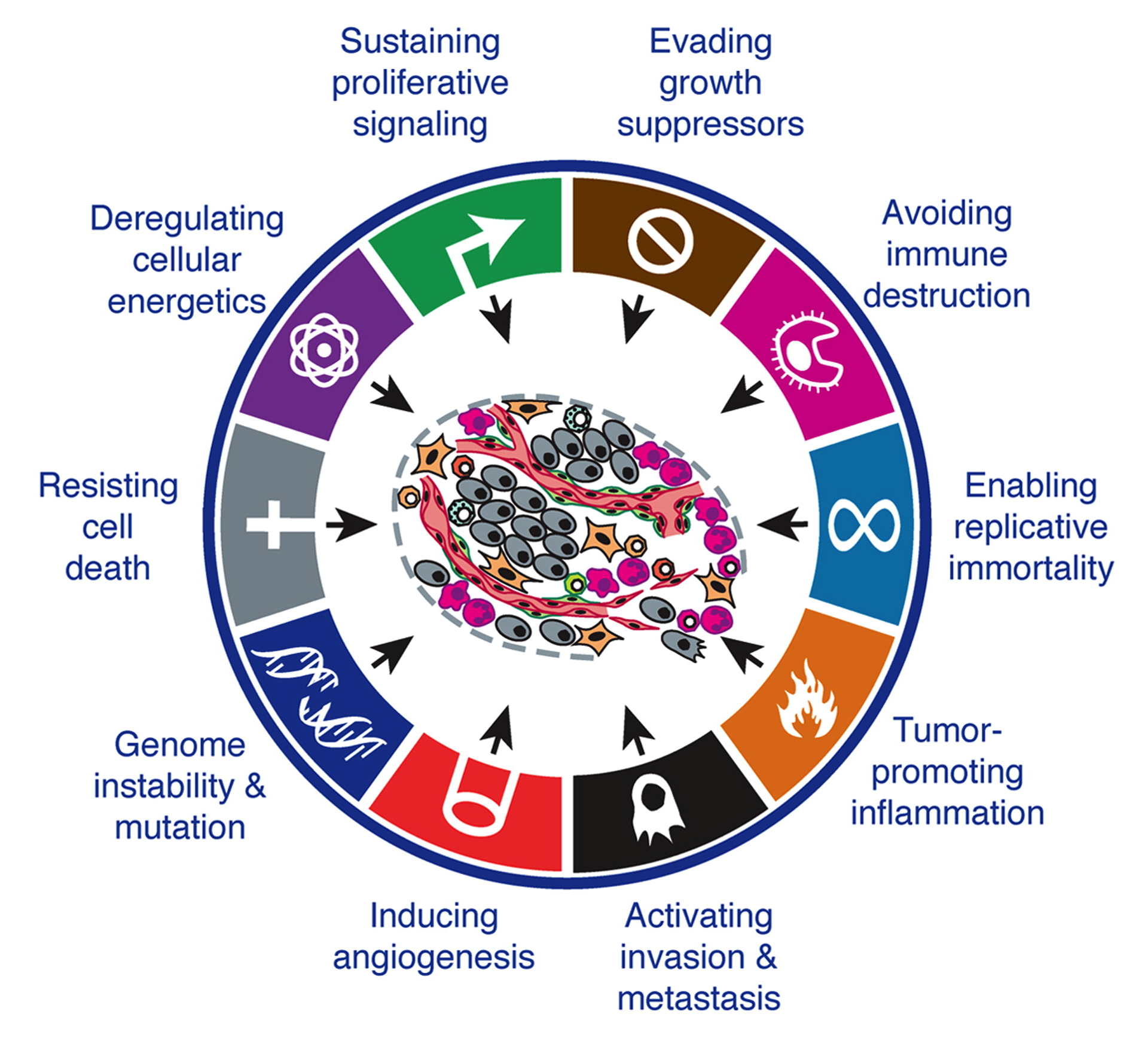

However, cancer is not a Mendelian disease for which it would be sufficient to identify the one and only gene responsible for deregulation. Indeed, the cell has many protective mechanisms. For example, if a genetic mutation appears in the DNA, it has a very high chance of being repaired by dedicated mechanisms. And if it is not repaired, other mechanisms will take over to trigger the programmed death of the cell, called apoptosis, before it can proliferate wildly. So a cancer cell is probably a cell that has learned to resist this cell death. Similarly, in order to generate excessive growth, a cell will need to be able to replicate itself many times. However, there are pieces of sequences on chromosomes called telomeres that help to limit the number of times each cell can replicate. A cancer cell will therefore have to manage to bypass this protection. Thus we can schematically define the properties that must be acquired by the cancereous cells in order to truly deviate the machinery. In an influential article, these properties were summarized in six hallmarks (Figure 2.5) which are: resisting cell death, enabling replicative immortality, sustaning proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, activating invasion and inducing angiogenesis (Hanahan and Weinberg 2000). Two new ones were subsequently added in the light of advances in knowledge (Hanahan and Weinberg 2011): deregulating cancer energetics and avoiding immne destruction. The acquisition of these capacities generally requires many genetic mutations and is therefore favoured by an underlying genome instability or tumor-promoting inflammation.

Figure 2.5: Hallmarks of cancer. The different biological capabilities acquired by cancer cells. Adapted from Hanahan and Weinberg (2011).

Each of these characteristics, or hallmarks, constitutes a research program in its own right. And for each one there are genetic alterations. These are tissue-specific or not, specific to a hallmark or common to several of them (Hanahan and Weinberg 2000). In any case, cancer can only result from the combination of different alterations that invalidate several protective mechanisms at the same time. This is often part of a multi-step process of hallmark acquisition that has been experimentally documented in some specific cases (Hahn et al. 1999) or more recently inferred from genome-wide data for human patients (Tomasetti et al. 2015). In summary, it appears that in order to study the functioning of cancer cells it is necessary to look at several mechanisms and to be able to consider them not separately but together, in as many different patients as possible. This ambitious programme has been made possible by a technological revolution.

2.4 The new era of genomics

2.4.1 From sequencing to multi-omics data

In 2001, the first sequencing of the human genome symbolized the beginning of a new era, that of what will become high-throughput genomics (Lander et al. 2001; Venter et al. 2001). From the end of the 20th century, biological data started to accumulate at an ever-increasing rate (Reuter, Spacek, and Snyder 2015), feeding and accelerating cancer research in particular (Stratton, Campbell, and Futreal 2009; Meyerson, Gabriel, and Getz 2010). The ability to sequence the human genome as a whole, for an ever-increasing number of individuals, has enabled less biased and more systematic studies of the causes of cancer (Lander 2011). The number of genes associated with cancer increased drastically and some very important genes such as BRAF or PIK3CA have been identified (Davies et al. 2002; Samuels et al. 2004). Progress also extended to the gene expression data. Gene-expression arrays have made an important contribution by providing access to transcriptomic data (RNA), i.e., what has been transcribed from DNA and is therefore one step further in terms of biological information. This information has made it possible to further explore the differences between normal and tumor cells (Perou et al. 1999), or even to refine the classification of cancers, which until now has been done mainly according to the tumor site. Breast cancers are thus divided into subtypes with different combinations of molecular markers that facilitate the understanding of clinical behavior (Perou et al. 2000). One step further, we also note the appearance of prognostic gene signatures such as gene expression patterns correlated with the survival of patients (Van’t Veer et al. 2002). This revolution was then extended to other types of data such as proteins (proteomics), reversible modifications of DNA or DNA-associated proteins (epigenomics), metabolites (metabolomics) and others, each representing a perspective that can complement the others to better understand biological mechanisms, particularly in the case of diseases (Hasin, Seldin, and Lusis 2017). We have thus entered the era of multi-omics data (Vucic et al. 2012).

2.4.2 State-of-the art of cancer data

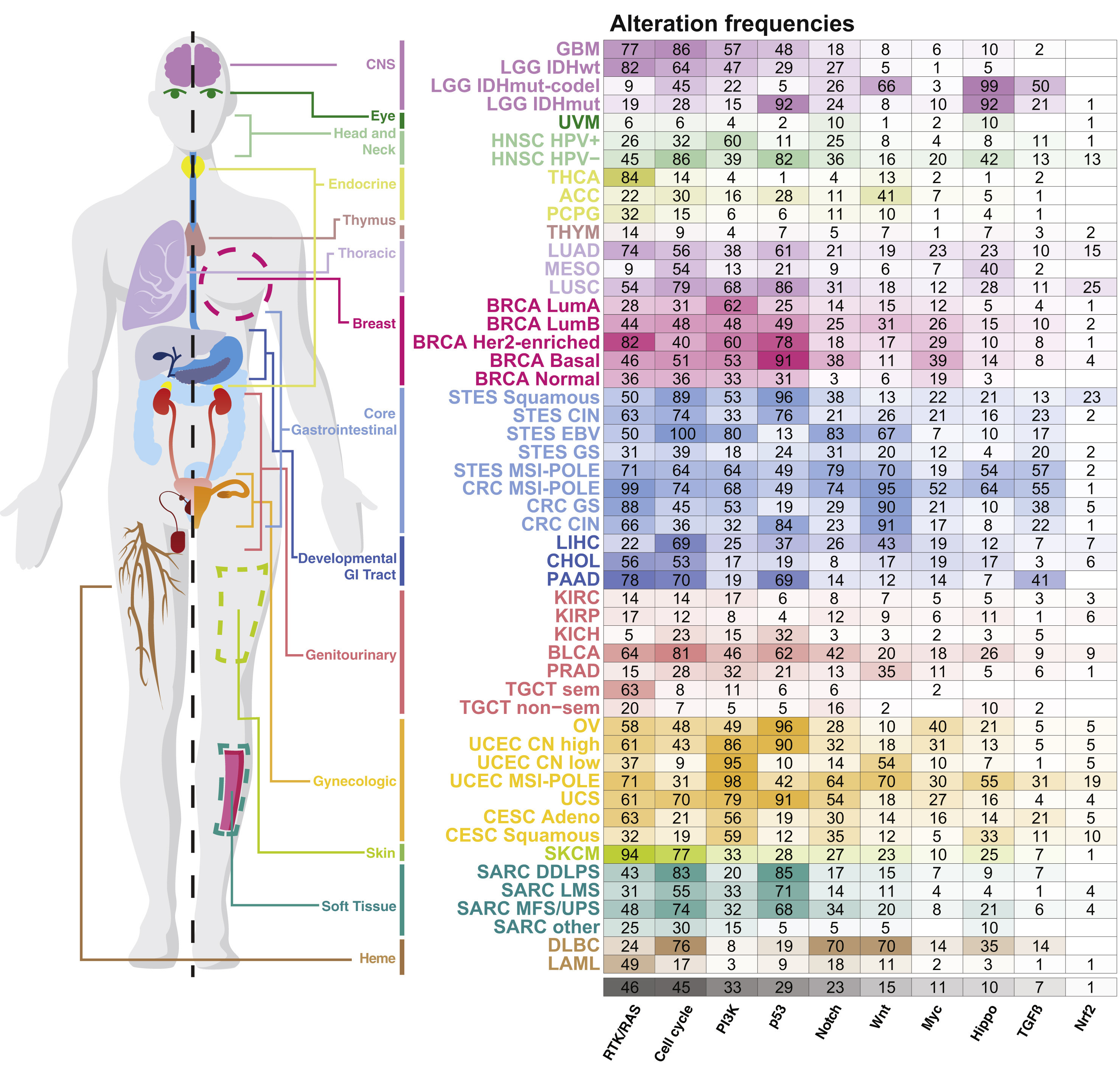

With respect to cancer in particular, this wealth of data is particularly represented by a family of studies conducted by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) consortium, started in 2008 (Network and others 2008). Cohorts of several hundred patients are thus sequenced over the years for different types of cancer (TCGA and others 2012), resulting today in a total of 11,000 tumors from 33 of the most prevalent forms of cancer (Ding et al. 2018). Figure 2.6 provides a partial but striking overview of the depth of data available under this program. We can see the frequencies of alterations of certain groups of genes for a list of cancer types, making it possible to visualize the disparities already anticipated in section 2.2 based on patient survival. There are indeed important differences between the organs but also between the different subtypes associated with the same organ. And this representation only corresponds to one layer of data, that of genetic alterations. It could be used for transcriptomic, epigenomic or proteomic data, thus giving rise to an incredibly complex photography.

Figure 2.6: Genetic alterations frequencies for cancer types from TCGA data. Frequencies of alteration per pahway and tumor types as summaried in Pan-cancer analyses from TCGA data. Reprinted from Sanchez-Vega et al. (2018).

However, the diversity of data available for cancer research extends far beyond this, both in terms of technology and type of data. This may be data from model organisms such as mice or even tumors of human origin made more suitable for experimentation. In the latter category, it is crucial to mention the huge amount of data available on cell lines, extracted from human tumors and transformed to be studied in culture. It is then possible to go beyond descriptive data and vary the experimental conditions in order to study the responses of these cells to perturbations and to enrich our knowledge. This provides an opportunity to know the response to more than 100 drugs of about 700 cell lines (Yang et al. 2012). The richness of these data, coupled with the omic profiling of each cell line, enables to study the determinants of response to treatment with unprecedented scope (Iorio et al. 2016). More recently, but following a similar logic, other types of inhibition screenings have been proposed based on a more specific technique called CRISPR-Cas9 (Behan et al. 2019). The simplicity of the cell lines in relation to the original tumors makes all these studies possible but sometimes hinders the clinical application of the knowledge acquired. For this reason, other types of biological models have been developed, including patient-derived xenografts (PDX) which is an implant of human tumors in mice to ensure the existence of a certain tumor microenvironment (Hidalgo et al. 2014), while maintaining drug screening possibilities (Gao et al. 2015). These two types of data, cell lines and PDX, have been used in this thesis, in addition to TCGA patient data, thus justifying the limitation of this presentation, which could otherwise be extended to other types of biological models. Similarly, other technologies are becoming increasingly important in the generation of cancer data, such as single-cell sequencing (Navin 2015), but will not be used in this work.

2.5 Data and beyond: from genetic to network disease

All that remains to be done now is to make sense of all these data, to organize them, because cancer understanding does not flow directly from the abundance of data, and the ability to produce it may have been outpaced by the ability to analyze it (Stadler et al. 2014). A striking example is that of the prognostic signatures mentioned above. The many signatures or lists of genes proposed, even for the same cancer type, share relatively few genes, are difficult to interpret and their efficiency is sometimes poorly reproducible (Domany 2014). Even more surprisingly, most signatures composed of randomly selected genes were also found to be associated with patient survival (Venet et al. 2011). One of the main avenues for improving the interpretability of the data is the integration of the prior knowledge we have of the phenomena, especially in the case of cancer (Domany 2014).

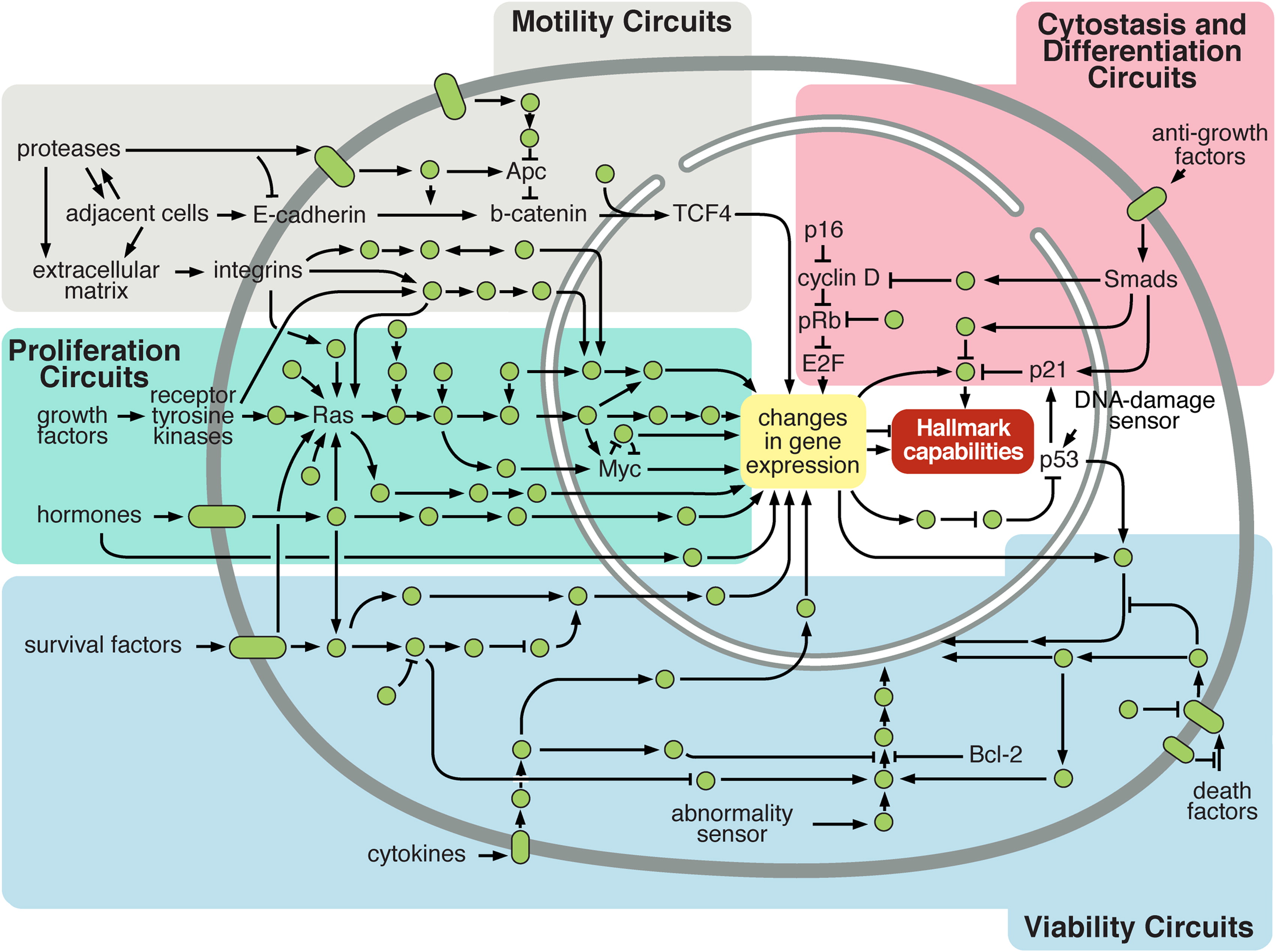

Figure 2.7: Simplistic representation of cellular circuitry. Normal cellular circuit sand sub-circuits (identified by colours) can be reprogrammed to regulate hallmark capabilities within cancer cells. Reprinted from Hanahan and Weinberg (2011).

This a priori knowledge is in fact already present in Figure 2.6 since genetic alterations have been grouped in several categories called pathways. A pathway is a group of biological entities and associated chemical reactions, working together to control a specific cell function like apoptosis or cell division. The interest of these groupings may be understood based on the description of hallmarks. Indeed, if the "aim" of a cancer cell is to inactivate each of the protective functions, then it is more relevant to think not by gene but by function. Inactivating only one of the genes associated with the function may be sufficient and it is no longer necessary to inactivate the others. Numerous alterations in a large number of genes in various patients result often in the same key impaired pathways, like alterations of cell cycle or angiogenesis for instance (Jones et al. 2008). It is therefore possible to improve the stability and interpretability of analyses by moving from the gene scale to the pathway scale (Drier, Sheffer, and Domany 2013). More generally, the integration of biological knowledge often leads to improved performance in various cancer-related prediction tasks, either through the selection of variables or by taking into account the structure of the variables (Bilal et al. 2013; Ferranti, Krane, and Craft 2017). Increasingly, the biological variables are not interpreted separately but in relation to each other (Barabasi and Oltvai 2004). This is reflected in the emergence of more and more resources to summarize and represent signaling pathways and associated networks such as SIGNOR (Perfetto et al. 2016) or the Atlas of Cancer Signaling Network (Kuperstein et al. 2015). Like other diseases, cancer then goes from a genetic disease to a network disease (Del Sol et al. 2010) and one can study how all kinds of genetic alterations affect the wiring of these networks (Pawson and Warner 2007), and modify the cellular functions leading to the previously described cancer hallmarks as depicted schematically in Figure 2.7. In short, the richness of the data did not make it less necessary to use prior knowledge in order to make the analyses more interpretable and more robust.

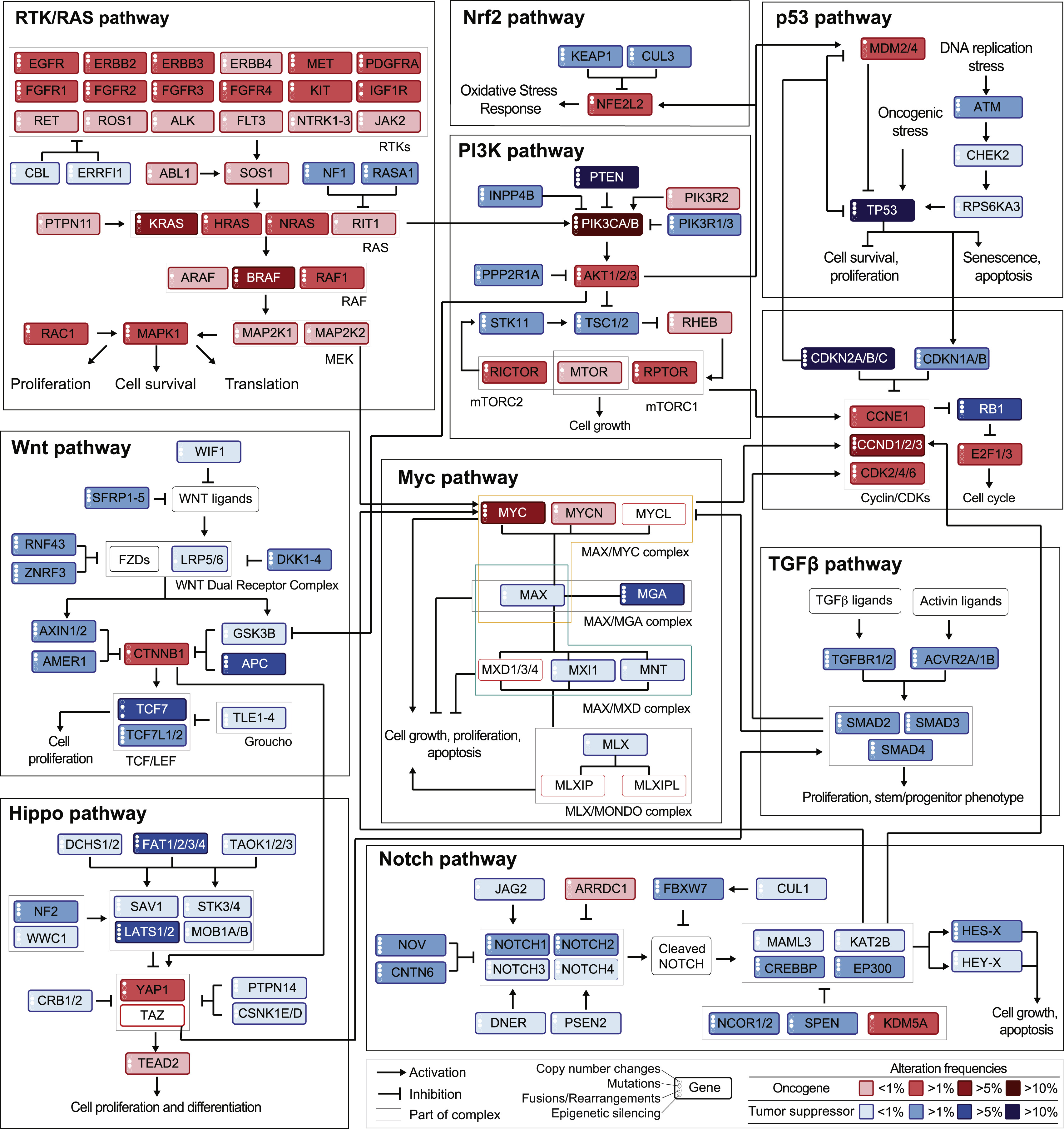

Figure 2.8: Genetic alterations frequencies from TCGA data mapped on a schematic signaling network. Frequencies of alteration per pathway and tumor types as summarized in Pan-cancer analyses from TCGA data. Reprinted from Sanchez-Vega et al. (2018).

The final step, to obtain one of the most complete and integrated visions of cancer biology, is then to integrate omics knowledge with knowledge about the structure of pathways to try to understand in detail how their combinations can lead to so many cancers that are both similar and different. An example of such a representation is given by mapping the TCGA data about genetic alterations, presented in Figure 2.6, on a representation of the different pathways showing not only their internal organization but also their cross-talk (Sanchez-Vega et al. 2018). This representation is proposed in Figure 2.8 and is one of the most recent and comprehensive view of the kind of tools and data available to the modeler who wants to dissect more deeply the mechanisms involved in cancer.

Summary

Cancer is more than ever seen as a genetic disease. Its appearance in a patient results from the accumulation of various genetic alterations that invalidate the protective mechanisms naturally intended to prevent uncontrolled proliferation. The simultaneous consideration of the numerous biological entities involved and the regulatory networks that link them calls for global systems biology methods. Technological developments also provide access to different types of omics data (genes, RNA, proteins, etc.) that provide complementary information, the joint analysis of which allows us to better understand the complexity of the mechanisms involved. It should be noted that many physical models of cancer (cell lines) extend the field of experimentation and generate data.

References

Alberts, Bruce, Alexander Johnson, Julian Lewis, Martin Raff, Keith Roberts, and Peter Walter. 2007. “Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science.” New York 1392.

Barabasi, Albert-Laszlo, and Zoltan N Oltvai. 2004. “Network Biology: Understanding the Cell’s Functional Organization.” Nature Reviews Genetics 5 (2). Nature Publishing Group: 101–13.

Behan, Fiona M, Francesco Iorio, Gabriele Picco, Emanuel Gonçalves, Charlotte M Beaver, Giorgia Migliardi, Rita Santos, et al. 2019. “Prioritization of Cancer Therapeutic Targets Using Crispr–Cas9 Screens.” Nature 568 (7753). Nature Publishing Group: 511.

Bianucci, Raffaella, Antonio Perciaccante, Philippe Charlier, Otto Appenzeller, and Donatella Lippi. 2018. “Earliest Evidence of Malignant Breast Cancer in Renaissance Paintings.” The Lancet Oncology 19 (2). Elsevier: 166–67.

Bilal, Erhan, Janusz Dutkowski, Justin Guinney, In Sock Jang, Benjamin A Logsdon, Gaurav Pandey, Benjamin A Sauerwine, et al. 2013. “Improving Breast Cancer Survival Analysis Through Competition-Based Multidimensional Modeling.” PLoS Computational Biology 9 (5). Public Library of Science.

Braithwaite, Peter Allen, and Dace Shugg. 1983. “Rembrandt’s Bathsheba: The Dark Shadow of the Left Breast.” Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 65 (5). Royal College of Surgeons of England: 337.

Bray, Freddie, Jacques Ferlay, Isabelle Soerjomataram, Rebecca L Siegel, Lindsey A Torre, and Ahmedin Jemal. 2018. “Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries.” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 68 (6). Wiley Online Library: 394–424.

Cohrs, Randall J, Tyler Martin, Parviz Ghahramani, Luc Bidaut, Paul J Higgins, and Aamir Shahzad. 2015. “Translational Medicine Definition by the European Society for Translational Medicine.” Elsevier.

Crick, Francis. 1970. “Central Dogma of Molecular Biology.” Nature 227 (5258). Nature Publishing Group: 561–63.

Davies, Helen, Graham R Bignell, Charles Cox, Philip Stephens, Sarah Edkins, Sheila Clegg, Jon Teague, et al. 2002. “Mutations of the Braf Gene in Human Cancer.” Nature 417 (6892). Nature Publishing Group: 949–54.

Del Sol, Antonio, Rudi Balling, Lee Hood, and David Galas. 2010. “Diseases as Network Perturbations.” Current Opinion in Biotechnology 21 (4). Elsevier: 566–71.

Ding, Li, Matthew H Bailey, Eduard Porta-Pardo, Vesteinn Thorsson, Antonio Colaprico, Denis Bertrand, David L Gibbs, et al. 2018. “Perspective on Oncogenic Processes at the End of the Beginning of Cancer Genomics.” Cell 173 (2). Elsevier: 305–20.

Domany, Eytan. 2014. “Using High-Throughput Transcriptomic Data for Prognosis: A Critical Overview and Perspectives.” Cancer Research 74 (17). AACR: 4612–21.

Drier, Yotam, Michal Sheffer, and Eytan Domany. 2013. “Pathway-Based Personalized Analysis of Cancer.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (16). National Acad Sciences: 6388–93.

Dulbecco, Renato. 1986. “A Turning Point in Cancer Research: Sequencing the Human Genome.” Science 231. American Association for the Advancement of Science: 1055–7.

Ferranti, Dana, David Krane, and David Craft. 2017. “The Value of Prior Knowledge in Machine Learning of Complex Network Systems.” Bioinformatics 33 (22). Oxford University Press: 3610–8.

Gao, Hui, Joshua M Korn, Stéphane Ferretti, John E Monahan, Youzhen Wang, Mallika Singh, Chao Zhang, et al. 2015. “High-Throughput Screening Using Patient-Derived Tumor Xenografts to Predict Clinical Trial Drug Response.” Nature Medicine 21 (11). Nature Publishing Group: 1318.

Hahn, William C, Christopher M Counter, Ante S Lundberg, Roderick L Beijersbergen, Mary W Brooks, and Robert A Weinberg. 1999. “Creation of Human Tumour Cells with Defined Genetic Elements.” Nature 400 (6743). Nature Publishing Group: 464–68.

Hajdu, Steven I. 2011a. “A Note from History: Landmarks in History of Cancer, Part 1.” Cancer 117 (5). Wiley Online Library: 1097–1102.

Hajdu, Steven I. 2011b. “A Note from History: Landmarks in History of Cancer, Part 2.” Cancer 117 (12). Wiley Online Library: 2811–20.

Hajdu, Steven I. 2012a. “A Note from History: Landmarks in History of Cancer, Part 3.” Cancer 118 (4). Wiley Online Library: 1155–68.

Hajdu, Steven I. 2012b. “A Note from History: Landmarks in History of Cancer, Part 4.” Cancer 118 (20). Wiley Online Library: 4914–28.

Hajdu, Steven I, and Farbod Darvishian. 2013. “A Note from History: Landmarks in History of Cancer, Part 5.” Cancer 119 (8). Wiley Online Library: 1450–66.

Hajdu, Steven I, and Manjunath Vadmal. 2013. “A Note from History: Landmarks in History of Cancer, Part 6.” Cancer 119 (23). Wiley Online Library: 4058–82.

Hanahan, Douglas, and Robert A Weinberg. 2000. “The Hallmarks of Cancer.” Cell 100 (1). Elsevier: 57–70.

Hanahan, Douglas, and Robert A Weinberg. 2011. “Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation.” Cell 144 (5). Elsevier: 646–74.

Hasin, Yehudit, Marcus Seldin, and Aldons Lusis. 2017. “Multi-Omics Approaches to Disease.” Genome Biology 18 (1). BioMed Central: 83.

Heijblom, Michelle, Linda M Meijer, Ton G van Leeuwen, Wiendelt Steenbergen, and Srirang Manohar. 2014. “Monte Carlo Simulations Shed Light on Bathsheba’s Suspect Breast.” Journal of Biophotonics 7 (5). Wiley Online Library: 323–31.

Hidalgo, Manuel, Frederic Amant, Andrew V Biankin, Eva Budinská, Annette T Byrne, Carlos Caldas, Robert B Clarke, et al. 2014. “Patient-Derived Xenograft Models: An Emerging Platform for Translational Cancer Research.” Cancer Discovery 4 (9). AACR: 998–1013.

Iorio, Francesco, Theo A Knijnenburg, Daniel J Vis, Graham R Bignell, Michael P Menden, Michael Schubert, Nanne Aben, et al. 2016. “A Landscape of Pharmacogenomic Interactions in Cancer.” Cell 166 (3). Elsevier: 740–54.

Jemal, Ahmedin, Elizabeth M Ward, Christopher J Johnson, Kathleen A Cronin, Jiemin Ma, A Blythe Ryerson, Angela Mariotto, et al. 2017. “Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2014, Featuring Survival.” JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 109 (9). Oxford University Press: djx030.

Jones, Siân, Xiaosong Zhang, D Williams Parsons, Jimmy Cheng-Ho Lin, Rebecca J Leary, Philipp Angenendt, Parminder Mankoo, et al. 2008. “Core Signaling Pathways in Human Pancreatic Cancers Revealed by Global Genomic Analyses.” Science 321 (5897). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 1801–6.

Kuperstein, I, E Bonnet, HA Nguyen, D Cohen, E Viara, L Grieco, S Fourquet, et al. 2015. “Atlas of Cancer Signalling Network: A Systems Biology Resource for Integrative Analysis of Cancer Data with Google Maps.” Oncogenesis 4 (7). Nature Publishing Group: e160–e160.

Lander, Eric S. 2011. “Initial Impact of the Sequencing of the Human Genome.” Nature 470 (7333). Nature Publishing Group: 187–97.

Lander, Eric S, Lauren M Linton, Bruce Birren, Chad Nusbaum, Michael C Zody, Jennifer Baldwin, Keri Devon, et al. 2001. “Initial Sequencing and Analysis of the Human Genome.” Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Liu, Jianfang, Tara Lichtenberg, Katherine A Hoadley, Laila M Poisson, Alexander J Lazar, Andrew D Cherniack, Albert J Kovatich, et al. 2018. “An Integrated Tcga Pan-Cancer Clinical Data Resource to Drive High-Quality Survival Outcome Analytics.” Cell 173 (2). Elsevier: 400–416.

Meyerson, Matthew, Stacey Gabriel, and Gad Getz. 2010. “Advances in Understanding Cancer Genomes Through Second-Generation Sequencing.” Nature Reviews Genetics 11 (10). Nature Publishing Group: 685–96.

Network, Cancer Genome Atlas Research, and others. 2008. “Comprehensive Genomic Characterization Defines Human Glioblastoma Genes and Core Pathways.” Nature 455 (7216). Nature Publishing Group: 1061.

Nowell, Peter C. 1976. “The Clonal Evolution of Tumor Cell Populations.” Science 194 (4260). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 23–28.

Pawson, T, and N Warner. 2007. “Oncogenic Re-Wiring of Cellular Signaling Pathways.” Oncogene 26 (9). Nature Publishing Group: 1268–75.

Perfetto, Livia, Leonardo Briganti, Alberto Calderone, Andrea Cerquone Perpetuini, Marta Iannuccelli, Francesca Langone, Luana Licata, et al. 2016. “SIGNOR: A Database of Causal Relationships Between Biological Entities.” Nucleic Acids Research 44 (D1). Oxford University Press: D548–D554.

Perou, Charles M, Stefanie S Jeffrey, Matt Van De Rijn, Christian A Rees, Michael B Eisen, Douglas T Ross, Alexander Pergamenschikov, et al. 1999. “Distinctive Gene Expression Patterns in Human Mammary Epithelial Cells and Breast Cancers.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 96 (16). National Acad Sciences: 9212–7.

Perou, Charles M, Therese Sørlie, Michael B Eisen, Matt Van De Rijn, Stefanie S Jeffrey, Christian A Rees, Jonathan R Pollack, et al. 2000. “Molecular Portraits of Human Breast Tumours.” Nature 406 (6797). Nature Publishing Group: 747–52.

Reddy, E Premkumar, Roberta K Reynolds, Eugenio Santos, and Mariano Barbacid. 1982. “A Point Mutation Is Responsible for the Acquisition of Transforming Properties by the T24 Human Bladder Carcinoma Oncogene.” Nature 300 (5888). Nature Publishing Group: 149–52.

Reuter, Jason A, Damek V Spacek, and Michael P Snyder. 2015. “High-Throughput Sequencing Technologies.” Molecular Cell 58 (4). Elsevier: 586–97.

Samuels, Yardena, Zhenghe Wang, Alberto Bardelli, Natalie Silliman, Janine Ptak, Steve Szabo, Hai Yan, et al. 2004. “High Frequency of Mutations of the Pik3ca Gene in Human Cancers.” Science 304 (5670). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 554–54.

Sanchez-Vega, Francisco, Marco Mina, Joshua Armenia, Walid K Chatila, Augustin Luna, Konnor C La, Sofia Dimitriadoy, et al. 2018. “Oncogenic Signaling Pathways in the Cancer Genome Atlas.” Cell 173 (2). Elsevier: 321–37.

Stadler, Zsofia K, Kasmintan A Schrader, Joseph Vijai, Mark E Robson, and Kenneth Offit. 2014. “Cancer Genomics and Inherited Risk.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 32 (7). American Society of Clinical Oncology: 687.

Stratton, Michael R, Peter J Campbell, and P Andrew Futreal. 2009. “The Cancer Genome.” Nature 458 (7239). Nature Publishing Group: 719–24.

TCGA, and others. 2012. “Comprehensive Molecular Portraits of Human Breast Tumours.” Nature 490 (7418). Nature Publishing Group: 61.

Tomasetti, Cristian, and Bert Vogelstein. 2015. “Variation in Cancer Risk Among Tissues Can Be Explained by the Number of Stem Cell Divisions.” Science 347 (6217). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 78–81.

Tomasetti, Cristian, Luigi Marchionni, Martin A Nowak, Giovanni Parmigiani, and Bert Vogelstein. 2015. “Only Three Driver Gene Mutations Are Required for the Development of Lung and Colorectal Cancers.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (1). National Acad Sciences: 118–23.

Van’t Veer, Laura J, Hongyue Dai, Marc J Van De Vijver, Yudong D He, Augustinus AM Hart, Mao Mao, Hans L Peterse, et al. 2002. “Gene Expression Profiling Predicts Clinical Outcome of Breast Cancer.” Nature 415 (6871). Nature Publishing Group: 530–36.

Venet, David, Jacques E Dumont, Vincent Detours, and others. 2011. “Most Random Gene Expression Signatures Are Significantly Associated with Breast Cancer Outcome.” PLoS Comput Biol 7 (10): e1002240.

Venter, J Craig, Mark D Adams, Eugene W Myers, Peter W Li, Richard J Mural, Granger G Sutton, Hamilton O Smith, et al. 2001. “The Sequence of the Human Genome.” Science 291 (5507). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 1304–51.

Vucic, Emily A, Kelsie L Thu, Keith Robison, Leszek A Rybaczyk, Raj Chari, Carlos E Alvarez, and Wan L Lam. 2012. “Translating Cancer ‘Omics’ to Improved Outcomes.” Genome Research 22 (2). Cold Spring Harbor Lab: 188–95.

Watson, James D, and Francis HC Crick. 1953. “Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids.” Nature 171 (4356): 737–38.

Weinberg, Robert A. 2013. The Biology of Cancer. Garland science.

Yang, Wanjuan, Jorge Soares, Patricia Greninger, Elena J Edelman, Howard Lightfoot, Simon Forbes, Nidhi Bindal, et al. 2012. “Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (Gdsc): A Resource for Therapeutic Biomarker Discovery in Cancer Cells.” Nucleic Acids Research 41 (D1). Oxford University Press: D955–D961.